Nail in the Coffin

A short story by Honora Quinn

One Last Teatime with Millicent McCraw

by Mercy Reid-Viletta for The Avalon Inquirer

Millicent McCraw will die on Tuesday. “If,” as she told me, “everything goes to plan.”

Over her forty-year writing career, McCraw has continuously invited us back into her fictional world of Camelot, Connecticut—the setting for her decades-spanning mystery series, The Rowans. The series has long been a point of contention, while widely praised for its “realistic” portrayals and dynamics between the four Rowan kids, McCraw’s own children have frequently criticized her blatant use of their lives for her novels, which only grew as the series progressed. According to her eldest daughter Tracy Turner, “[McCraw] left no skeleton in the closet, no traumatic stone unturned, and no juvenile misstep forgotten.”

Yet, we love McCraw’s creation, despite—or maybe in spite of—the decades of personal pain she has caused. We attempt to forgive her because she is one of the greats of our generation, because of all our fond memories wrapped up with her turmoil. Book 115, The Rowans: Nail in the Coffin, is meant to be McCraw’s grand farewell, and after publishing she will “retreat from the limelight,” according to her publisher Keene and Dixon in a press release from last fall. I was invited to conduct Millicent McCraw’s final interview, after which she said she would be “as good as dead.”

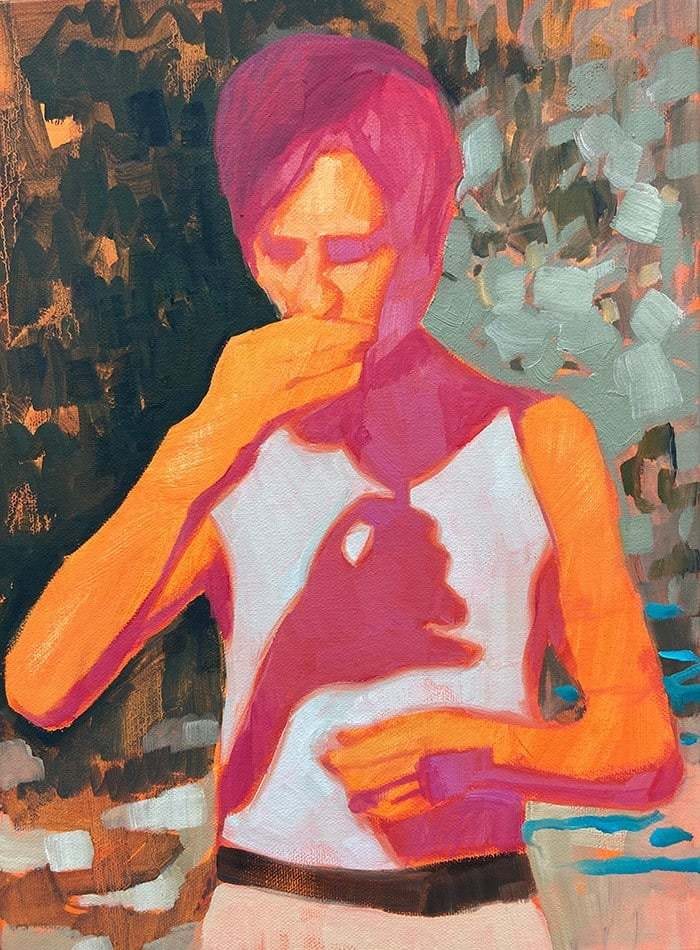

The author is waiting for me, hovering just inside the threshold of her home. The air smells of rotting wood, of cigarettes, of dish soap—not the baked goods and salt I always equivalated with this sorry, old house. She is just as poised and perfect as ever and my first thought, like always, is that she looks like Lucille Ball. Her wardrobe, largely unchanged since I met her as a child, cements her in the past, torn out of one of the many photos that line the dark hall. Light blots of makeup cover petrified flesh, a silk scarf is carefully tied around patches of vanishing hair, and she is dripping in a curated mix of costume and legitimate finery. She ushers me into the study, planting me in the overstuffed “guest chair” before taking her own seat across from me. In all my years of meeting with her, I had never seen her desk so bare. Her typewriter and pens are pushed neatly into the corners, and the usual mountain of manuscripts or reading material has been replaced with a dusty tea set. She’s ready to move on and is both literally and figuratively cleaning the house before she goes.

As we sipped from the cups and crunched on stale crackers, I cut to the chase.

“Do you regret it?”

“Many things. What is on your mind in particular?” She knows exactly what I mean, but I continue.

“That you spent a lifetime creating fictional children which lead you to neglect and strain your relationships with your own?”

Her mouth forms a thin line.

“No. I know they don’t see it this way, but [The Rowans] gave them everything; it has said what I cannot.”

She sips. The end of her phrase hangs between us. She has read Say It Back by Elaine Ballard. We all have. Hell, I got to interview Ballard about it. The essay collection by her youngest child is often known as the “first nail in the coffin,” of the end of McCraw’s career. It did what no exclusive profile, no press statement, nor private conversation could do—it showed us all what transpired within the McCraw’s “semi-public circus,”, and, for once, we actually believed it.

She coughs. “Surely, they have made enough money off it all to forgive me by now.”

“Is that why you’re stopping the gravy train? That’s why you’re pulling the plug on the series, on your writing? Because you think you’ve given your children enough?” The unsaid end to the question floats in the air: Do you think this will make them back off and stop ruining your empire?

“Not at all. When I was young, I thought I would write forever. In fact, I thought that up until a couple of months ago. My current book deal [with Keene and Dixon] was meant to go for at least five more novels.”

“Then why?”

“I’m dying, Ms. Reid. And we have seen what happens to authors with unfinished business.”

She waves a hand around like a specter.

“I’d rather finish the series myself and craft a definite conclusion than have my children and every wannabe-mystery-man riffle through my files and attempt to pin something together out of the incoherent ramblings that are bound to come in the next few months. All it can do is ruin what I have spent so much time and effort trying to build.”

“So, you’re sick?”

She nods, wiping a dark lipstick stain from the lip of her mug.

“It’s not a total surprise. I watched my mother die when I was about your age. She faded away in the public eye, horribly and raw. Typically, I’d prefer to follow her lead like with most things. But she had nothing to leave behind but a few pleasant memories. Me, I’m at risk of losing everything. Today, I am comfortable, I have—most of—my wits. My beauty has lessened, of course, but I think I have reached a comfortable plateau. So, why not pull myself away while I still can? While I’m still loved by someone out there.”

She points toward the study door.

“You’re very caught up in legacy. Hiding yourself away is one way to go about it, but you’re leaving behind three children and seven grandchildren—at least. How do you think they will remember you?”

“We went through this game before, Mercy. I regret a lot of what has transpired over the years, but I hope they can understand how this happened, that this was not due to a lack of love—quite the opposite. I hope they will remember me as an artist and the good that happened, even if it wasn’t in our home, in front of their eyes.”

I sit forward in my chair. “Can you elaborate?”

She pushes back in her own. “No. I think I should ‘quit while I’m ahead.’”

“Then why don’t we talk about the book instead?” I reach for my copy tucked under the chair, but McCraw extends a hand to stop me.

“It’s all we’ve been talking about. This book is me, letting the kids move on. All of them.”

I stall for a moment at that, at the layers she is intentionally employing. In letting go of her children, flesh and blood, along with the fictional, she is simply severing ties to make sure they cannot meddle after she goes.

I sit back now; the book tumbles through my fingers onto the ugly, bronzy, and shag carpet.

“That’s all?” My tone turns more aggressive, but I never lose my grasp on civility. “You’re going out with a whimper just so you can get the last word?”

She sips her tea, surprised—fascinated even—at my outburst.

“Ms. Reid, I will do what it takes to win.”

Nowhere on her face did she seem to grasp that motherhood has no winners, that her children were not opponents, that they were not her pawns. Nowhere on her face did she seem to understand all of this could have been avoided had she just said, “I love you,” even one more time.

She swept away the tea set soon after, and I could hear her shoveling it away from my seat in her office. It was her daughter’s room once upon a time, the circus-themed wallpaper peaking around the corners of her formidable shelves. In winning in this moment, she saw herself as superior to her adult children, yes. But you must understand: She saw herself winning over the 13-year-old girl who lived in that room, who ran away in the dead of night in hopes that her mother’s narrative would stop trapping her. Winning over the little boy named after his dead brother and heroic father, who learned the hard way that you can never beat a ghost. And over her perpetual baby, the once precocious little girl who knew that words and work would always matter more than her. Yet when she let me out of her house, which was probably minutes away from falling off into the sea, she smiled. She smiled like she did when I was a girl, wanting and dreaming of becoming a writer, a legend just like her.

It’s hard for me to wrap my head around these dueling narratives and the utter complexity of Mrs. McCraw. How is it that one woman can be a brilliant writer, an estranged mother, a dying widow, and a self-appointed god, all at the same time? My image of her is jumbled and warped but, in the end, she did get what she wanted.

Millicent McCraw got the last word, even if it put the final nail in her coffin.

Honora Quinn (she/her) is an undergraduate student pursuing a degree in English and Classical Studies. She is the host of On The Shelf with Honora Quinn, a literary podcast where she asks authors tough questions—like what kind of plate they are. Her nonfiction has been published by StarTrek.com and Polyester Zine. Her fiction can be found in the pages of Dreamworldgirl Zine.